EDITORIAL - In the rural Central California city of Madera, Thomas Jefferson Junior High principal Benny Barsotti was concerned that one of his teachers did not show up for school or call in for a substitute. This was highly unusual for this teacher, who chaired the school's English department and was hired thirteen years earlier from the Stanford University Graduate Program. The teacher lived alone, just three houses south of the school, so Barsotti walked over to see if everything was all right. First, he knocked on the front door, but there was no answer. Then, he noticed the teacher's car was not in the driveway. For some reason, Barsotti walked around the house to the backyard and looked through two French doors that looked into the living room. He then got on his school radio and told the school secretary to call the police immediately.[1]

EDITORIAL - In the rural Central California city of Madera, Thomas Jefferson Junior High principal Benny Barsotti was concerned that one of his teachers did not show up for school or call in for a substitute. This was highly unusual for this teacher, who chaired the school's English department and was hired thirteen years earlier from the Stanford University Graduate Program. The teacher lived alone, just three houses south of the school, so Barsotti walked over to see if everything was all right. First, he knocked on the front door, but there was no answer. Then, he noticed the teacher's car was not in the driveway. For some reason, Barsotti walked around the house to the backyard and looked through two French doors that looked into the living room. He then got on his school radio and told the school secretary to call the police immediately.[1]

When Officer Sam Anderson arrived at the house three minutes later, he was directed to the backyard, where he attempted to gain entry. Once inside, he found what appeared to be a body covered by a large bath towel, leaning on the front door in a seated position on the floor, where a large pool of blood had formed. The officer noticed the wall and door behind the body were covered in blood splatter, with bloody handprints down the hallway to the back of the house and a trail of blood to the home's only bathroom. When the officer removed the towel, he found the bludgeoned nude body of Glenn Reitz, the 35-year-old missing teacher. Anderson placed the towel back on top of Reitz’s head and body as he found it, then backed out of the house while calling for a supervisor and two of the department's detectives.[2] Once detectives arrived and the crime tape went up, the rumors began, and this teacher, who always placed the needs of his students first, went from a position of respect to becoming that gay teacher who was killed in Madera.

While being gay in California gained more acceptance since voters shot down the 1978 Briggs Initiative, which would have banned gay teachers in California’s public schools, in the 1980s conservative Central Valley, being a gay teacher still held a negative bias in the eyes of many of the general public. Not to mention the bias that allowed local law enforcement to conduct raids on establishments that catered to the gay community or stings to entrap gay men for solicitation of sexual activities in public places. For thirteen years, Reitz had concealed a secret life in Madera that many of his friends and family would have difficulty believing. For Reitz, this secret in the closet life was the only way he could maintain the job in public education that he loved while seeking in the shadows the need for companionship that every person craves. In the end, the dangers in these shadows and his secret would eventually cost him his life.

Historiography

Tom Warner argues in his book Never Going Back that even after the repeal of gay sodomy laws, the courts and law enforcement maintained a negative bias toward such activities. He asserts that the courts and law enforcement had years of viewing gays in one light. That change was not going to happen overnight, especially when the predominant stereotype was that gays would attempt to solicit children into their lifestyle. Gays were still viewed as ‘others,’ and that viewpoint was ingrained in society for hundreds of years.[3] Timothy Stewart-Winter writes in his essay Queer Law and Order: Sex, Criminality, and Policing in the Late Twentieth-Century, that the gay rights movement gained some traction after the 1969 uprising at New York's Stonewall Tavern. Meanwhile, white middle-class gays still faced capricious punishment in other raids where their names would be published in local newspapers, outing their involvement in the gay community to the general public and jeopardizing their positions within the hetero-normal community.[4] Both authors suggest that raids in gay bars began to diminish in the 1980s, and entrapment operations began to increase.

Warner also argued that a report on law enforcement's belief that homosexuals had no place in the rank and file of policing as they saw the acts of homosexuality as a sick perversion. The report went on to list stereotypes that were incompatible with police work.[5] In his book Pink Blood, Douglas Victor Janoff argues that when homosexual communities found law enforcement less than willing to investigate gay-biased hate crimes, the community began to stand up with volunteers in pink berets and police whistles patrolling gay communities to provide the protection the police would not. He also explains that some law enforcement agencies would underreport the amount of gay-based hate crimes in targeted communities, even going so far as to say there were no issues with crime in one gay community when, in actuality, there was an active case of a serial killer targeting gays that the police were not investigating.[6]

For teachers in the mid-1970s, being outed would be a death sentence to one's career. In Stuart Biegel’s book The Right to Be Out, he asserts that homosexual teachers of the time would find themselves being excluded from employment if it ever came out that they were living an LGBT lifestyle. The rights some thought they had on paper were not the reality for many teachers, exposing a systematic bias rooted in the educational system. In 1978, teachers in California had another threat to their livelihoods in the Briggs Initiative that sought to ban gay teachers from the classroom.[7] This Lavender Scare, like the Red Scare of the 1950s, targeted ‘out’ gay teachers and would have forced them back into the closet or out of public education.[8] Around this time, throughout the United States, efforts were being made to include sexual orientation in the list of protected classes in teacher's employment contracts. In Tina Fetner’s essay, Working Anita Bryant: The Impact of Christian Anti-Gay Activism on Lesbian and Gay Movement Claims, she asserts that the Briggs Initiative would have made those contracts invalid in California, ending the careers of thousands of gay teachers.[9]

Closeted gay teachers were in a catch-22 where they could come out and fight against the initiative, but if they lost, they would be on a list of the first teachers fired.[10] In Gay Teachers Fight Back written by Sara Smith-Silverman, she states that the backers of Briggs had raised nearly a million dollars to ensure the measure passed, while the opponents of the initiative were waging a grassroots effort raising only a little more than one hundred thousand dollars, That grassroots effort eventually garnered the support of labor unions and former California Governor Ronald Reagan.[11] With grassroots organizers Sally Gearhart, a professor from San Fransisco State College, and San Fransisco Supervisor Harvey Milk, gays were encouraged to come out so the public would realize everyone knows someone from the gay community, hence lessening the impact of stereotypes.[12] In the essay How Sweet It Is!, Jackie M. Blount exposes Briggs's real goal to attack the low-hanging fruit of California’s gay teachers to catapult his chances at beating then-Governor Jerry Brown in the next election. In reality, what Briggs actually did was give the national gay movement the spark it needed to expand its reach and plant the seeds of acceptance for the gay community with the heteronormative community.[13] Unfortunately, less than a month after the defeat of Briggs, Supervisor Harvey Milk was gunned down in his office at the San Fransisco City Hall along with the city’s mayor by former police officer and city supervisor Dan White.

The fear of coming out is actually a fear of having one’s homosexual life exposed and the implied or perceived losses that might come from that exposure. In her 2005 essay The Problem of Coming Out, Mary Lou Rasmussen argues that for many, the closet lifestyle is a zone of shame or exclusion. Still, it offered safety from biases affecting one's open life. Coming out might cause other issues that must be factored in, such as losing work or financial security.[14] Tony Adams agrees in his essay Paradoxes of Sexuality, Gay Identity, and the Closet that coming out of the closet for homosexuals can be a perilous situation negotiating the invisible closet self with the public heteronormative self.[15] In their book Sexual Science and Clinical Practice, Richard Friedman and Jennifer Downey agreed that the layers of compromise formations of self-valuing in the invisible closet might lead to an unmasculine self-representation in one's later public life.[16] A homosexual lifestyle might instill an incompatibility with religious faiths or parental expectations that manifest into self-hatred that would force someone to remain in the closet, hidden from society, afraid to expose who they really are. Living a secret life, away from the people who really love you, might even put you in dangerous situations that may very well cost you more than just exposure.

* * *

While, in general, the population of the United States has become more accepting of the homosexual community, there is evidence that this community still faces significant anti-gay bias, prejudice, and discrimination within certain aspects of everyday life, such as employment, civil rights, and law enforcement.[17] The biases homosexuals have had to deal with for the past forty years related to law enforcement, institutional, and self-bias have had the ultimate effect of keeping homosexuals in the closet where they were safe from their real-life exposure to the community, but at what cost?

Perhaps it was the public bias toward gay teachers that caused Glenn Reitz to hide his real life from his friends and family. The research supports the idea that a fear of negative bias from law enforcement might expose his secret, ending his career or worse. The police report of the murder shows Reitz was dealing with the personal demons of self-bias based on the conflict between his Catholic religious upbringing and family expectations with a lifestyle that contradicted those beliefs. Ultimately, a combination of these biases caused him to create a life away from his friends and family that would place him in the company of people who would prove dangerous to his own safety. Because this 35-year-old teacher was not allowed to live an open life outside the closet, fear of these biases and how they might cost him his job put him in a position that cost him much more. It cost him his life.

Law Enforcement Bias

Nearly forty years after the bludgeoned body of teacher Glenn Reitz was found in his Madera home, no one has been brought to justice for his murder. No new information has been added to the reams of paper that make up the Madera Police Department’s official report since 1988, except for a one-page letter written to the detective sergeant of the department by the victim’s cousins seventeen years after the murder. In 2002, Reitz’s cousin, Elizabeth Ashford, met with Detective Sergeant Ken Alley to review the police report. During their meeting, Alley was candid about what he knew of the history of the case, and Ms. Ashford followed up with a letter to Alley that is the only record that the meeting ever took place. That letter indicates that the Madera Police knew who the murderer was, as it was part of a string of killings by a known serial killer. While some evidence found at the crime scene was never submitted to the FBI or the California Department of Justice, other evidence was contaminated by an infestation of rats in the Fresno DOJ Crime lab. Miss Ashford believed the case was ultimately shelved because the sexual orientation of the victim conflicted with the religious beliefs of the city’s chief of police.[18]

Glenn Reitz was a respected teacher in the Central California community of Madera. He rose through the ranks at the city’s only junior high school to become the school’s English department chairman. Every year, he took students to his alma mater, Stanford University, for sporting events and informal school tours. He worked with the Boy Scouts of America to form the city’s first drum and bugle corps for high school students. He was fitness conscious, working out at the local gym six days a week, and enjoyed the outdoors, whether snow or water skiing. He had many friends in Madera, but none knew his secret. Glenn was a gay man living in the conservative Central Valley who frequented Fresno gay bars, bath houses, and truck stops looking for companionship. That might not have been an issue in California’s Bay Area or today’s more open and inclusive community. Still, in the Central Valley of the 1980s, like other areas of California, that information might have ended his career in education or caused problems from law enforcement that showed a bias towards what would eventually be called the LGBT community throughout the state.

During an October 23rd, 1989, protest of former California Governor Pete Wilson’s veto of a gay rights bill outside of the Century City Plaza Hotel, Los Angeles Police in full riot gear with nightsticks dispersed a crowd of five hundred LGBT protestors, arresting several and hospitalizing a few. The bill would have ended the practice of using undercover police officers in setting up ‘stings’ to arrest gay men for what law enforcement called lewd behavior. Just eight months after the 1991 videotaped beating of motorist Rodney King by several officers from the LAPD, a California Senate subcommittee hearing on ‘police conduct and gender bias in law enforcement’ was held in West Hollywood. Attorney John Duran, who was representing recently outed, fired, and prosecuted Los Angeles County Sheriff Deputy Bruce Boland for being gay, testified, “Gay men who are prosecuted for lewd conduct are then generally subject to other forms of discrimination like losing teaching licenses. We have seen them losing the ability to practice the law, losing the ability to deal with children, and all based upon false accusations from police officers caught up in vice squad stings. This needs to stop, and it will stop.”[19]

Jon Davidson, a senior counsel for the A.C.L.U., told the state panel he was at the Century City police riot and barely escaped the beatings of the nightsticks but saw many who were not so lucky. He was at a press conference soon after the incident where then Los Angeles Police Chief Darryl Gates called lesbians and gay men unnatural and said none of his officers would want to work with a homosexual if they ever had one apply to his department. Gate’s assistant police chief Robert Vernon was a little less elegant when he expanded on his boss’s sentiment of hiring gay police officers, “Homosexuals have a corrosive influence upon their fellow employees because they attempt to entice normal individuals to engage in perverted sex practices.”[20]

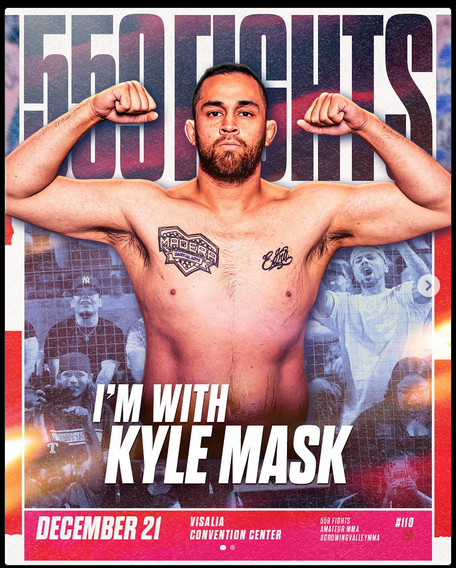

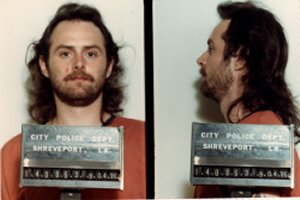

Certain aspects of the Ashford letter to Madera Police stand out as suspect because the investigation ended soon after Reitz’s stolen car turned up in Louisiana in 1988.[21] This was also when a new name started appearing in the police report: Darrell Crider. Ashford felt the police knew who their suspect was and that he was a serial killer in his 20s.[22] Crider was arrested in California following a violent year throughout the Southwestern United States. Bodies were popping up from Florida to Arizona, all gay, beaten to death, nude but covered with a towel, and having their cars and wallets stolen. In 1988, Shreveport Louisiana Police Detective Gary Alderman guessed Crider’s body count was around fifteen, “I always thought there would be more victims. Every time I hear of an unsolved transient-related murder from the time, I wonder if Darrell was involved."[23]

Certain aspects of the Ashford letter to Madera Police stand out as suspect because the investigation ended soon after Reitz’s stolen car turned up in Louisiana in 1988.[21] This was also when a new name started appearing in the police report: Darrell Crider. Ashford felt the police knew who their suspect was and that he was a serial killer in his 20s.[22] Crider was arrested in California following a violent year throughout the Southwestern United States. Bodies were popping up from Florida to Arizona, all gay, beaten to death, nude but covered with a towel, and having their cars and wallets stolen. In 1988, Shreveport Louisiana Police Detective Gary Alderman guessed Crider’s body count was around fifteen, “I always thought there would be more victims. Every time I hear of an unsolved transient-related murder from the time, I wonder if Darrell was involved."[23]

Today, Darrell Crider is serving a life sentence for murder in a Louisiana prison. He escaped in 1999 with three other prisoners but was soon rounded up and moved to the maximum-security wing of the prison facility in Angola. He was also convicted of murder in Florida and Arizona, is now facing an indictment in Texas for four more murders in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, and is the prime suspect for homicides in Colorado, New Mexico, and California.[24] Since Crider’s arrest in early 1986, he has yet to be interviewed by Madera Police regarding the murder of Glenn Reitz. Today, his body count has increased to nineteen from his 1985 nationwide killing spree.[25]

Just one year before Reitz’s murder, Madera Police Sergeant Mike Jeffries wrote a report about an attack on Reitz in his home. Reitz met this man in a Fresno bar in February of 1984, then invited the younger Merced man to his house for drinks the next month. Things soon started to go bad; at some point, Dennis David Bergeron pulled a handgun out of his backpack and forced Reitz into his bedroom, where he bound the teacher's hands and feet with tape while he lay on his bed. While Reitz was tied up, the suspect ransacked his house looking for valuables. Reitz was able to unbind himself with a small hatchet from his bedroom closet and forced the suspect from the house. When Sergeant Jeffries arrived, the suspect had fled the scene, and Reitz, knowing an investigation would have been public and called into question his sexuality, wished no formal action to be taken at that time.[26]

What might the outcome of an investigation gain Reitz when other jurisdictions throughout the country were ignoring gay-based crimes? In Dallas, Texas, two gay men were shot and killed at a local park where gays would congregate. When the killer was sentenced to thirty years instead of the usual life sentence, Republican Judge Jack Hampton told the Dallas Times Herald, “I do not much care for queers cruising the streets picking up teenage boys. I put prostitutes and gays at about the same level. And I would be hard put to give somebody life for killing a prostitute."[27] Around the same time, up north in Quebec, Montreal Police issued a press release claiming the crime in the city’s Gay Village was lower than in surrounding areas. However, activists claimed law enforcement was purposely underreporting gay hate crimes. They stated that there were at least two assault cases per week, ranging from punching to knife attacks, and attacks outside village gay bars were on the increase. Claims were also made that the police were homophobic, allowing a serial killer to run free in the village, killing thirteen in a two-year span. One magazine reporter wrote, ”If this were thirteen teenage girls killed, heads would be rolling.”[28]

In Ashford’s letter, she acknowledges that because Reitz was a homosexual in a conservative community, the public and police might tend to forget a case of this nature, but that she believes Reitz deserved more than he has received in the way of justice. In an interview with her father, James Ashford claims Alley stated that Gordan Skeels, the Madera Police Chief at the time, stopped the investigation when it hit a dead end in 1988. He also states Alley said Skeels was a member of the Mormon Church, and the chief felt enough time had already been spent on this ‘gay’ murder. Alley denies this claim, but one might wonder how Ms. Ashford or her father, who never met Chief Skeels and did not have friends in Madera, knew the chief was Mormon.[29] It might have also been as simple as Alley misspoke. Skeels may have just known their suspect was Crider and knew he would never be a free man in this lifetime and, if extradited and convicted, would never serve a day in a California prison. Was it worth the time and expense of a lengthy trial to prosecute a man who already will never be free from prison and who would never serve a day for the Reitz murder?

State-Based Bias and the 1978 Briggs Initiative

Just four years after the Madera Unified School District hired Reitz, a state referendum was placed on the ballot for voters to decide if gays and people who supported the gay movement should be allowed to teach in California. This proposition, known as the 1978 Briggs Initiative or Proposition 6, was a product of a similar measure decided in Florida just a year earlier.[30] In Florida’s Dade County, a local ordinance was enacted that would prohibit discrimination in employment and housing on the basis of sexual orientation. Anita Bryant, a 1960s singer and spokesperson for the Florida Citrus Commission, organized the Baptist-based ‘Save Our Children’ campaign to overturn the Dade County ordinance. The campaign was based on the conservative Christian beliefs of the immorality and sinfulness of homosexuality and the threat of homosexual recruitment of children to the lifestyle of sexual molestation.[31] Bryant wrote in her book At Any Cost, “What these people really want, hidden behind obscure legal phrases, is the legal right to propose to our children that theirs is an acceptable alternate way of life…. I will lead such a crusade to stop it as this country has not seen before. The recruitment of our children is absolutely necessary for the survival and growth of homosexuality… for since homosexuals cannot reproduce, they must recruit, must freshen their ranks…. If gays are granted rights, next we will have to give rights to prostitutes and to people who sleep with St. Bernards.”[32]

Bryant’s Florida campaign was just the beginning of an organized anti-gay movement that spread across the country with the help of people like the Reverend Jerry Falwell and the beginnings of what would become his pro-Christian group, the Moral Majority, and California State Senator John Briggs. Both went to Florida to help Bryant’s movement and campaign to repeal the ordinance. When the Florida voters rescinded the pro-gay ordinance by a margin of 69-31 percent, similar measures arose in St. Paul, Minnesota; Wichita, Kansas; and Eugene, Oregon. However, the true battleground for this gay rights issue would ultimately be in California.[33] At a press conference announcing the referendum, Briggs told reporters, “If you would put a second-grade child with a homosexual, you are off your gourd. We do not let necrophiliacs be morticians. We have got to be crazy to allow homosexuals who have an affinity for young boys to teach our children."[34] Briggs saw the California initiative that would bear his name as an opportunity to catapult himself into the state spotlight, increasing his chances of challenging sitting governor Jerry Brown in the next election.[35] Briggs and Bryant would play on existing gay stereotypes and biases to illicit fear in voters’ minds that gays were grooming children for sexual molestation. He told voters that teachers were role models to students, and they would use that position to recruit kids to choose a gay lifestyle. Up until three months before the November 7th election day, polls showed that Briggs was convincing the public about these demonizations and how the measure would more than likely pass.[36]

In 1977, San Fransisco camera shop owner Harvey Milk became the first openly gay person elected to public office in California. As a San Fransisco City Supervisor representing the Castro and Haight Ashbury districts, one of his first acts was passing a gay rights ordinance for the city. He saw this as a way of answering Bryant’s Florida win and getting a jump on Brigg’s planned referendum.[37] Milk, however, experienced frustration with middle-of-the-road LGBT community members who were reluctant to join the fight against Briggs. Many were afraid to come out because of the position it would put them in if Briggs were successful. Along with Milk, San Fransisco State College professor Sally Gearhart, gay activist Cleve Jones, and hundreds of others organized a grassroots effort to raise money and debunk the gay stereotypes Briggs was spreading. Milk warned that Briggs would not stop at attacking teachers but that a homophobic law like this one would propagate into more anti-gay legislation restricting the freedoms of the gay community as a whole.[38]

Briggs and Milk would debate Prop 6 in forums up and down the state during the campaign, each time Milk argued verifiable facts to Briggs's combative stereotypes and fearful biases. When Briggs asserted that gay teachers would groom their students into a gay lifestyle, Milk stated the statistics available from the FBI, the California Highway Patrol, the Los Angeles Police Department, and the San Francisco Police Department, which showed that heterosexuals, not gays, commit more than ninety percent of child molestations, often members of the child’s family.[39] Briggs claimed that homosexuality was a choice someone makes because of experiences and the influences in their lives. Milk responded, “One of those myths in this new ordnance is that you choose your sexuality. You do not choose your homosexuality. Like you do not choose blue eyes. Like you would choose your candidates.”[40] When Briggs talks about teachers being role models for children’s sexuality, Milk cites studies from reputable psychologists that showed a child’s sexual orientation is determined during its pre-school years or earlier. The significant role models are the mother and father. In one debate, Milk told the audience that he was raised in a strong heterosexual environment with heterosexual teachers and role models, so how is he gay? Milk added, “If it were true that children mimicked their teachers, you would sure have a helluva lot more nuns running around.”[41]

Five years earlier, the American Psychiatric Association announced it no longer considered homosexuality a mental illness. During the summer of 1978, former California Governor and future United States President Ronald Reagan came out against the Briggs Initiative, as did Presidents Gerold Ford and Jimmy Carter. Reagan wrote in a Los Angeles Herald-Examiner editorial six days before the vote, “Whatever else it is, homosexuality is not a contagious disease like the measles. Prevailing scientific opinion is that an individual's sexuality is determined at a very early age and that a child's teachers do not really influence this.”[42] Despite this effort, when Reagan became president a few years later, he did not have a very friendly gay record, actively ignoring the beginning of the AIDs crisis that began during his administration.[43]

Milk’s other tactic to fight Briggs was to show the public that these gay rights issues affected people close to them. He asked the gay community to come out to their friends and family in order to lessen the anti-gay bias culture that existed and show the community that real human lives were at stake.[44] "We can defeat the Briggs Initiative if all the gay people come out to your family, your friends if indeed they are your friends, your coworkers, your neighbors," Milk said at the time. "You will hurt them if you come out, but think of how they will hurt you if they vote for Briggs. If they do not come out, it will be a tight race."[45] While being down in the polls just three months before the election, voters rejected the initiative 58.4% to 41.6% across the state, defeating the proposition even in Briggs' own home district of Orange County.[46] The state's LGTB community, along with labor unions, feminists, and gay allies, organized a successful grassroots movement that defeated these homophobic biased arguments behind Proposition 6. Ironically, even as Milk won the battle over the Briggs Initiative, he would lose the war against homophobia. Just twenty days later, as he predicted in his prerecorded will, he was assassinated by a disturbed man’s bullet in his office at city hall.[47]

When former San Fransisco City Supervisor Dan White was convicted for the assassination of Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone, it was not for murder but voluntary manslaughter. He only served five years of a seven-year prison sentence for a crime that changed the face of California politics for decades.[48]

After the defeat of Briggs in the 1980s, being a gay teacher in California still did not guarantee any protection against a negative bias that could cost you your job. Being an outteacher in Madera County was still not an option for Reitz as Madera County was one of the only three counties in the Central Valley that overwhelmingly supported Proposition 6. Just like they did thirty-five years later with Proposition 8, the gay marriage ban, Madera, Tulare, and Kern County voters turned out in masses to support traditional Christian values.[49] While nearly four million voters rejected the ban on teachers Briggs offered, nearly three million voters saw no problem with the biased proposition.

There was very little a teacher could do if a school district did not want a particular person to continue working in their schools. A few months after Reitz was killed, Mack Johnson, a black basketball coach at Madera High School, was accused of sexual misconduct with a white female student. Despite all criminal charges being thrown out by Judge Paul Martin for lack of merit, Johnson was not allowed to return to a Madera classroom.[50] With the support of the district’s superintendent and board of trustees, the school's principal, Robert Warner, told Johnson he could have his back pay of $12k and the district would not seek to strip the coach of his teaching credential if he quietly resigned. Even after it was revealed in the media that the prosecutor, Paul Avent, was using the case to advance his career to a judgeship during that year’s election cycle, Johnson was out of a job.[51] Even with an unsubstantiated accusation against a protected class member, there was a difference between the rights one has on paper and those in the classroom.

Self-Bias and the Safety of the Invisible Closet

Between the years 1973 and 1978, Reitz sought treatment from Fresno psychiatrist Lance Boyce for issues the teacher was having coping with the self-bias of his sexuality. The doctor said Reitz had called his issue with being gay his “problem,” and he was sure no one from Reitz’s family knew he was gay. He confided in the doctor that occasionally, he would meet men at local adult bookstores or pick up hitchhikers along the freeway to bring back to his home. Dr. Boyce describes the men Reitz would be attracted to were not his equals, meaning they were usually younger. However, the doctor was confident that Reitz never mixed his sexual life with his school career. Boyce told police, to his knowledge, “He never fooled around” with anyone from school, his Boy Scout troop, or the drum and bugle corps. He said he believed that Reitz was discreet about his “problem.” The doctor continued to treat Reitz off and on after 1978, and he felt the teacher began to accept who he was over time.[52] It would be presumptuous to assume that one page of a police report could clarify everything about Reitz’s mental state concerning his homosexuality and if he feared coming out of the closet. All that is known is that Reitz was gay, and he kept that secret from his closest friends and family.

The act of coming out of the closet, or becoming aware of one's sexuality and beginning to disclose it to others, is a process that might take years for some people to experience. For many, the process of coming out is empowering and is the first step in effectively changing homophobic attitudes through one-to-one personal contact. Like Milk suggested during the Briggs campaign, coming out is a way of combating the negative prejudice against sexual identity minorities while increasing the well-being of gays, lesbians, and bisexuals.[53] However, there are many reasons why someone might want to remain in the safety of the closet, such as pressures of religious values or family expectations and the real or implied fear of losing employment or financial and emotional support from family and friends. At the time of his death, coming out was not necessarily an option for teachers like Reitz. Coming out and living an open life in the 1980s environment of the Central Valley would not have been a desired objective if he wanted to maintain his professional career.[54]

Coming out for the teacher is still a catch-22. While it might be empowering to be true to one's real self and a role model for teens facing their own sexuality questions, only twenty-one states prohibit workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation. In comparison, only eighteen states offer protections for transgender teachers. Teachers cannot rely on non-discrimination protections to mitigate the risk of coming out in the classroom.[55] Teaching contracts typically contain vague moral turpitude clauses, giving school districts broadly defined reasons for firing or not asking teachers to return. Gay teachers often felt silenced at work, fearing that coming out might threaten their job security or lead to alienation. Being forced to hide who you really are had serious psychological consequences.[56] While this country has become a more gay-friendly place to work, protecting children from the falsely perceived confusing or corrupting knowledge of LGBT issues has been very slow to change.[57]

While Reitz went to extremes to find companionship in those dark shadows, towards the end of his life, he was open to a real relationship with a man. At a Fresno State football game, Reitz met a male cheerleader by the name of Kent Byers. Byers was a local Sigma Chi fraternity member who met with Reitz in public spaces and occasionally spoke with the teacher on the phone. He told Madera Police he and Reitz had never been intimate, nor had he been to the teacher's Madera home. Reitz would purchase gifts for the Fresno State student, but Byers did not return his affection. He described Reitz as a loner seeking the right person to come into his life. According to Byers, Reitz thought the young cheerleader was that person, but Byers said he was not ready for a relationship and turned down Reitz’s advancements. A directory of members of the Fresno State chapter of Sigma Chi Fraternity was found in Reitz's home, and police learned that on the night of the murder, a phone call was made to the local chapter. Byers told police that he had spoken with Reitz on Sunday but not the night of the murder; he provided police with a list of all the members of the house he also knew to be gay.[58]

The issues Reitz must have been facing of self-bias based on the conflict between his Catholic religious upbringing and family expectations and that of his homosexuality were shown in the behaviors of his parents following his death. The Reitz parents were completely shocked when they learned their son was a homosexual. While most parents might want to know who killed their child, Francis Reitz wanted to know nothing about the case after police shared their revelation. Fresno attorney and Reitz's cousin, James Ashford, remembers that when Reitz’s mother was once asked if the police had learned anything new about the murder case, she said, “No, and I hope they never do.” At Reitz’s funeral, his father, Ralph Reitz, asked many of his son’s Madera friends how it could be true that his son was gay. Both of Reitz’s parents are buried next to him in a Sanger, California cemetery. Neither of them ever learned the identity of the person that killed their child.[59]

Conclusion

It was the fear of coming out and the public biases homosexuals experienced that forced Reitz into dangerous situations that would eventually cost him his life. The conservative Central Valley of the late 1970s through the mid-1980s would never allow a junior high school teacher to live an openly gay life and still maintain his career teaching children. Over the years, law enforcement has targeted homosexuals with raids on establishments they frequent and undercover entrapment stings to force them back into the closet into an invisible life. Conservative Christian organizations have tried to propagate false stereotypes of pedophilic teachers grooming students into a gay lifestyle. While on the surface, most of these stereotypes have been debunked, there is still an underlying concern in some conservative regions of the state when it comes to gay teachers in public education. These biases have caused extreme psychological consequences when they force people into lives that are not true to who they are.

The current generation has seen the closet doors open and familiar people come out. It is no longer a case of knowing someone who knew a homosexual in another town. Now, we know people who are gay in our family, neighborhood, and our everyday life. Mostly, people are no longer afraid to be who they are in their private lives publicly. Glenn Reitz had the right to live that life, but more importantly, he deserved justice and to have his murder solved. He had nothing but the best interests of his students in his heart, and in his death, he deserved more than he was given.

Notes

[1] Madera Police Department, “Initial report” Glenn Reitz Murder, Detectives Dale Padgett & David Foster. Case C85-522, Madera, California, 1985.

[2] Madera Police Department, “Initial report”, 1985.

[3] Tom Warner, “Never going back,” in Police representation and judicial homophobia (University of Toronto Press, 2002), 99.

[4] Timothy Stewart-Winter, “Queer law and order: sex, criminally, and policing in the late twentieth century,” in The Journal of American History vol 102. no. 1 (Oxford University Press, 2015), 64.

[5] Warner, “Never going back,” 103.

[6] Douglas Victor Janoff, “Urban Cowboys and Rural Rednecks,” in Pink Blood (University of Toronto Press., 2005), 209.

[7] Stuart Biegel, “Challenges for LGBT educators,” in The right to be out (University of Minnesota Press., 2010), 86.

[8] Biegel, “Challenges for LGBT educators” 79.

[9] Tina Fetner, “Working Anita Bryant: The impact of Christian anti-gay activism on lesbian and gay movement claims,” in Social Problems vol. 48 no. 3 (Oxford University Press, 2001), 417.

[10] Fetner, “Working Anita” 420.

[11] Sara Smith-Silverman, “Gay teachers fight back! Rank-and-file gay and lesbian teachers' activism against the Briggs initiative”, Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 29, no. 1, (University of Texas Press 2020). 10.

[12] Smith-Silverman, “Gay teachers fight back!,” 3.

[13] Jackie Blount, “How sweet It Is,” in Counterpoint vol. 367 (Peter Lang AG, 2012), 48.

[14] Mary Lou Rasmussen, “The problems with coming out,” Theory into Practice, vol. 43, no. 2, (Taylor & Francis LTD, 2004). 145.

[15] Tony Adams. “Paradoxes of sexuality, gay identity, and the closet.” Symbolic Interaction, vol. 33, no. 2 (Wiley, 2010), 235.

[16] Richard Friedman and Jennifer Downey, “Internalized homophobia and gender-valued self-esteem in the psychoanalysis of gay patients”, Sexual Orientation and Psychodynamic Psychotherapy, (Columbia University Press, 1995), 208.

[17] Kevin A. Callender. “Understanding antigay bias from a cognitive-affective-behavioral perspective.” Journal of Homosexuality. (Taylor & Francis Group, LLC 2015), 786.

[18] Elizabeth Ashford, Letter to Madera Police Detective Ken Alley, July 17, 2002.

[19] California Legislature; Senate judiciary subcommittee on peace office conduct, gender bias, West Hollywood, California. (November 6, 1991) 40.

[20] California Legislature, 46.

[21] Madera Police Department “Reitz car found” Glenn Reitz Murder, Detectives Dale Padgett & David Foster. Case C85-522, Madera, California, 1988.

[22] Ashford, Letter, 2002.

[23] Gary Alderman, Phone interview, October 19, 2022.

[24] Joe Hughes, “Missouri man wanted in beating here sought in 15 murders,” San Diego Union-Tribune, (October 23, 1985). B2.

[25] Gary Alderman, Phone interview, October 19, 2022.

[26] Madera Police Department, “Reitz assault” Glenn Reitz Murder, Seargent Mike Jeffries. Case C85-522, Madera, California, 1984.

[27] Christopher Haight, “The silence is killing us: Hate crimes, criminal justice, and the gay rights movement,” in The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, July 2016. Vol. 120. No. 1 (Texas State Historical Association., 2016), 27.

[28] Janoff, “Urban cowboys,” 211.

[29] James Ashford, Phone interview, October 15, 2022.

[30] Brice Pettit, “Briggs crushed,” Bay Area Reporter, Vol. 8 No. 23(November 1978). A2.

[31] B, Drummond Ayres Jr., “Miami votes 2 to 1 to repeal law barring bias against homosexuals,” New York Times, (June 8, 1977). A1.

[32] Anita Bryant, Bob Green, At any cost. Grand Rapids, Michigan, (Old Tappan, N.J.: Revell. 1978).

[33] Ayres Jr., A1.

[34] Sara Smith-Silverman, “Gay teachers fight back!”, 1.

[35] Blount, “How sweet It Is,” in Counterpoint vol. 367 (Peter Lang AG, 2012), 48.

[36] Jerry Gillam. “Gay teachers initiative qualifies: Briggs measure will be on November ballot.” Los Angeles Times (June 1, 1978), D1.

[37] Harvey Milk, “To beat Briggs,” in An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk’s Speeches and Writings (University of California Press., 2013), 221.

[38] Milk, “To beat Briggs,” 223.

[39] Harvey Milk, “Ballot argument against Proposition 6,” in An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk’s Speeches and Writings (University of California Press., 2013), 140.

[40] Harvey Milk, “Milk vs. Briggs televised debate transcript,” in An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk’s Speeches and Writings (University of California Press., 2013), 229.

[41] Milk, “Milk vs. Briggs televised debate transcript,” 228.

[42] Ronald Reagan, "Editorial: Two ill-advised California trends," Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. Los Angeles, California, (November 1, 1978) p. A19

[43] Dale Carpenter, "Reagan and gays: A reassessment," IGF Culture Watch. University of Minnesota Law School, (June 10, 2004), https://tinyurl.com/3zkwecky.

[44] Harvey Milk, “The positives or the negatives,” in An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk’s Speeches and Writings (University of California Press., 2013), 231.

[45] Truty Ring, “The Briggs initiative: remembering a crucial movement in gay history.” The Advocate. Los Angeles, California. (August 31, 2018), https://tinyurl.com/cndxccba.

[46] Brice Pettit, “Briggs crushed,” Bay Area Reporter, Vol. 8 No. 23(November 1978). A2.

[47] Harvey Milk, "Political will," recorded November 18, 1977, Harvey Milk Archives--Scott Smith Collection, GLC 35, Box 14, Folder 33. San Francisco Public Library, https://tinyurl.com/3cj75y4z.

[48] New York Times Archives, “Dan White gets 7 years 8 months in double slaying in San Fransisco,” New York Times, (July 4, 1979). A6.

[49] Chris Cillizza, “How Proposition 8 passed in California and why it wouldn’t today,” Washington Post, (March 26, 2013), https://tinyurl.com/mm74pspr.

[50] Darrell Maddox. “Judge dismisses sex charges after prosecutor screams at him.” Fresno Bee (April 19, 1986), A12.

[51] Cyndee Fontana. “Former MHS coach resigns teaching position.” Madera Tribune (May 6, 1986), A1.

[52] Madera Police Department, “Dr. Lance Boyce interview” Glenn Reitz Murder, Detectives Dale Padgett & David Foster. Case C85-522, Madera, California, 1985.

[53] Dee Bridgewater, “Effective coming out:” Self-disclosure strategies to reduce sexual identity bias. In J.T. Sears & W.L. (1997). 65.

[54] Mary Lou Rasmussen, “The problems with coming out,” Theory into Practice, vol. 43, no. 2, (Taylor & Francis LTD, 2004). 147.

[55] Catherine Connell, “Pride, prejudice and professionalism,” in Science in Society Quarterly, Fall 2015. Vol. 14. No. 4 (American Sociological Association., 2015), 37.

[56] Smith-Silverman, “Gay teachers fight back!”, 30.

[57] Smith-Silverman, “Gay teachers fight back!”, 30.

[58] Madera Police Department, “Kent Byers interview” Glenn Reitz Murder, Detectives Dale Padgett & David Foster. Case C85-522, Madera, California, 1985.

[59] James Ashford, Phone interview, October 15, 2022.